I will explain some of the features used to characterize the crystal compounds into perovskite or non-perovskite structures. The constructed features were fed to different Artificial Neural Networks, which classify the crystal compounds in a binary fashion. These features are constructed using the different atom-environments in a crystal compound. These environments are known as Wyckoff sites. The Wyckoff sites gather those atoms having the same point-symmetry group.

We need to find a way to tell the ANNs about the atoms located in the Wyckoff sites. One way is to associate an average atomic radius, r, and an electronegativity, χ, to each Wyckoff site. In fact, this approach is the essence of the features constructed in my research. Atomic radii are used as part as a first approximation. In future projects, it might be more accurate to use covalent radii or ionic radii. It is important to note that the ionic radii do not only depend on the oxidation state of the atom, but also on the coordination and geometry. For this reason, assigning ionic radii may become harder to non-symmetrical structures. Additionally, the assessment of the ionic radii is not trivial for compounds with transitional atoms.

Next, I will instance the characterization of the Wyckoff sites in terms of the atomic radii and electronegativity:

a) Consider that you have all the positions of a certain Wyckoff site, say they have the label a, fully occupied by the atoms Ti. In that case, those positions are characterized by the atomic radius and electronegativity of titanium. According to references 1 and 2, rTi=2.57 Å, and χTi = 1.54.

b) Consider the last situation but the titanium atoms are not occupying all the positions with Wyckoff label a. In this case, there are vacancies in the crystal compound. Assume that the occupation fraction of the sites with the label a by the titanium atoms is 0.8 (the fraction left corresponds to vacancies). Then, the average atomic radius and electronegativity of that Wyckoff site are 2.056 Å and 1.232, respectively.

c) It may occur that there are two different atoms, say titanium and zirconium, fully occupying the positions of the same Wyckoff site. This case happens in the compounds known as solid solutions. Let’s assume that the occupation fraction of titanium is 0.6, and 0.4 for zirconium. The atomic radii and electronegativity of Zr are 2.68 Å and 1.33. Then, the average atomic radius of that Wyckoff site is:

r = fTi*rTi + fZr*rZr

r = 0.6 * 2.57 Å + 0.4 * 2.68 Å

r = 2.614 Å

whereas the average electronegativity is 1.456.

d) Consider the case c), but there are vacancies in the positions of the Wyckoff site occupied by titanium and zirconium. Let’s assume that the occupation fraction of Ti and Zr are 0.5 and 0.3. The reader may prove that the average atomic radius and electronegativity of that Wyckoff are 2.089 Å and 1.169.

Thus, there are two features for each Wyckoff site of the crystal compound. Afterward, you may create a collection of crystal compounds having three Wyckoff sites. This collection will characterize the crystal compounds with six features (two per Wyckoff site). The ANN trained with this feature construction will be capable to manage perovskite compounds such as those of the space groups Pm3m and R3c (Last post). Similarly, a collection characterized with eight features corresponds to a collection of compounds with only four Wyckoff sites. This feature construction will allow you to train ANN capable to deal with perovskite compounds having the space groups Pnma or Fm3m. And so on. The number of feature tailors the length of the input data fed to the ANN. But what if it were possible to combine both sets of crystal compounds, the one with three and the other with four Wyckoff sites?

A possible way to homogenize the compounds to have the same number of sites is by appending extra sites with zero occupation. This extra site appending is only done with those compounds originally described with fewer Wyckoff sites. After appending, all compounds would be described with the same number of sites. Note that in the last sentence I only said sites and not Wyckoff sites. In fact, those sites are the sum of the original Wyckoff sites with the artificial zero occupied sites. A question you may have is about the ordering of the sites. In the approach I used, the sites appear according to their multiplicity, in ascending fashion. Then, the extra sites are appended before the original Wyckoff sites.

The compound TaSnO3 adopts the ideal perovskite structure (space group Pm3m). The CIF number in the Crystallography Open Database of this compound is 1001775. Tin atoms (χ = 1.96, r = 2.48 Å) occupy the Wyckoff sites a; tantalum atoms (χ = 1.50, r = 2.58 Å) occupy those Wyckoff sites with the label b; and the oxygen atoms (χ = 3.44, r = 1.71 Å) occupy the Wyckoff sites with the label c. The atomic radii and electronegativities of the species occupying the Wyckoff sites are accommodated as follows:

[[ 1.96 2.48],

[ 1.50 2.58],

[ 3.44 1.71]]

The rows correspond to the specie occupying the Wyckoff sites with label a, b, and c. Since the accommodation order is alphabetical, the multiplicity also increases. Note that the columns correspond to the average electronegativity and the atomic radius. The order of these columns can be changed and does not matter whenever the ANN has not been trained.

Now, assume that the compound TaSnO3 is part of a collection characterized with four sites. The last array becomes:

[[0.00 0.00],

[ 1.96 2.48],

[ 1.50 2.58],

[ 3.44 1.71]]

The extra zero occupied sites are added at the beginning of the array and the sites are order with increasing multiplicity. One row, one site.

Finally, suppose that the same TaSnO3 compound belongs to a collection characterized with eight sites. Then, the array would become:

[[0.00 0.00],

[0.00 0.00],

[0.00 0.00],

[0.00 0.00],

[0.00 0.00],

[ 1.96 2.48],

[ 1.50 2.58],

[ 3.44 1.71]]

For each compound of the collection, you get an array where each row contains info about electronegativity and atomic radius. The shape of the arrays is in all the compounds the same, since all the compounds were characterized with the same number of sites. Prior feeding the ANN with information about each compound, you need to unravel each array into a vector. This vector is your input data. The original array of TaSnO3 after unravelling looks like:

[ 1.96 2.48 1.50 2.58 3.44 1.71]

each vector element is:

[ χ1 r1 χ2 r2 χ3 r3 ]

where the subindices are related to each site. Similarly, if the array of TaSnO3 belongs to the collection characterized with four Wyckoff sites, the vector is:

[ 0.00 0.00 1.96 2.48 1.50 2.58 3.44 1.71]

Each vector element is:

[ χ1 r1 χ2 r2 χ3 r3 χ4 r4 ]

Note that the information concerning the first site is zero since this was the added site with zero occupation.

Up to here, the site characterization has been done with only two atomic properties. These atomic properties are not the only one to use for characterization, of course. You can experiment with other properties. The additional properties should have a relationship with the output values you model with your ANNs.

Electronegativity differences and radii quotients

One way to obtain more features is by combination. The easiest way to combine two features is using the elemental mathematical operations (addition, subtraction, product and quotient). Some of the features obtained by this approach may not have a clear chemical or crystallographic meaning. I will explain you some features you can obtain by combination, which have chemical meaning.

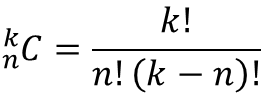

Recall the number of combinations formula:

where n is the number of elements in the set, and k is the number of elements in the subset you form. In the case where the collection of crystal compounds is characterized with four sites (n = 4), the number of different pairs (combination by two elements) are six. With four different electronegativities (χ1, χ2, χ3, and χ4), the six pairs possible are:

- χ1, χ2

- χ1, χ3

- χ1, χ4

- χ2, χ3

- χ2, χ4

- χ3, χ4

The same can be established for the atomic radii.

With the electronegativity pairs it is possible to form differences. The electronegativity differences are related to the bond nature. The bond can be either ionic or covalent. The predominance of a bond type characterizes some solid materials. For the collection characterized with four sites, the electronegativity differences are:

- χ1 – χ2

- χ1 – χ3

- χ1 – χ4

- χ2 – χ3

- χ2 – χ4

- χ3 – χ4

Similarly, with the atomic radii pairs it is possible to form quotients. The quotients are related to the geometry defined by the first neighbors around a central atom. For the collection characterized with four sites, the atomic radii pairs are:

- r1/r2

- r1/r3

- r1/r4

- r2/r3

- r2/r4

- r3/r4

It is possible to form combinations by pairs with the six pairs of atomic radii formerly found. After using the number of combinations formula, 15 different pairs of atomic radii pairs can be obtained. With the 15 combinations it is possible to form atomic radii pair sum-quotients. The meaning of these quotients is related to packing efficiency in a crystal compound. One of the most famous packing factors used is the Goldschmidt tolerance factor, which is used to assess if a compound can adopt a perovskite structure. The next table summarizes all the features which can be constructed with the collection characterized with four sites.

Some results

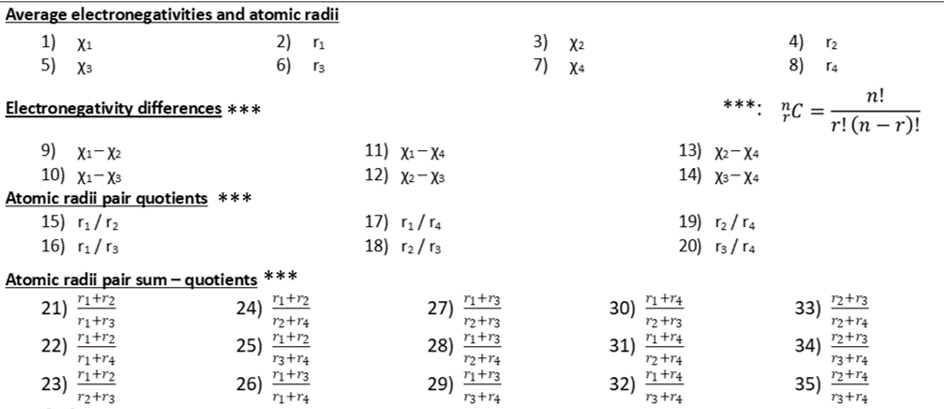

The next Figure shows the results obtained with a collection characterizing the crystal compounds with four sites. The collection contained 2868 crystal compounds. The half of the collection were perovskite compounds (the remaining compounds did not have the perovskite structure). The metrics of precision, recall and F1-score were obtained with all the compounds of the training and cross-validation sets, once the training was complete.

The next week I will talk about some limitations of the feature characterization described here and how to tackle them. I will also show you other results that I presented two years ago in the IX National Crystallography Congress, in Oaxaca, Mexico.

References

- Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 14625 -14632

- William M. Haynes. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 100 Key Points. CRC Press, London, 95th edition, 2014